Promise.all is stinky

8/13/2023I think we can all agree that asynchronous code is a beast. The moment the control flow becomes non-sequential, when it feels like lines are not being sequentially executed, it becomes a nightmare to debug or even reason about. This is why we have promises, to help us tame the beast. But even promises tend towards satanic behavior when we need to await a set of them before we allow our code to proceed its execution. This is where Promise.all comes in.

A quick run-down on promises 🤝

Promises are a pattern for handle asynchronous code in a more synchronous manner. They are a way to represent a value that will potentially be available in the future. Fundamentally, they encapsulate some state: pending, fulfilled, or rejected. When pending, we have no value, when fulfilled, the Promise has a value, and when rejected, the Promise has an error. Likewise, promises should also have a way to handle each of these states - essentially callbacks that are called when the state changes.

I'll be using JavaScript/TypeScript promise implementation for this explanation, but fundamentally it should be the same for any language implementing this pattern.

The Promise class

This class essentially encapsulates our fulfilled, pending and rejected states. It has a constructor that takes a function with two arguments:resolve and reject. These are the callbacks that are called when the Promise is fulfilled or rejected. Likewise, the Promise allows the developer to register callbacks for when the Promise is fulfilled or rejected. These are the then and catch methods respectively.

const p = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve('Hello World!');

})

})

.then((value) => console.log(value))

.catch((err) => console.log(err));

Promise is fulfilled when the timeout is complete (no argument was passed, so this will just be instant, however will still deviate from the usual synchronous flow). The then method is called with the value passed toresolve, and the catch method is never called.Sweet sweet syntactic sugar (like a 100% sugar boba): async and await 🥺

It's almost universally acknowledged that using callbacks for handling asynchronous control flow is asking for a brisk and painful death. This is where the rather miserably neologised term "callback hell" comes from. See artwork below:

getUser(1)

.then((user) => {

getPosts(user.id)

.then((posts) => {

posts.forEach((post) => {

getComments(post.id)

.then((comments) => {

comments.forEach((comment) => {

getReplies(comment.id).then((replies) => {

replies.forEach((reply) => {

getLikes(reply.id).then((likes) => {

console.log(`there are a few likes ${likes.length}`)

})

.catch((err) => {

console.error(`Failed to fetch likes for reply ${reply.id}: ${err}`);

});

});

}).catch((err) => {

console.error(`Failed to fetch replies for comment ${comment.id}: ${err}`);

});

})

})

.catch((err) => {

console.error(`Failed to fetch comments for post ${post.id}: ${err}`);

});

});

})

.catch((err) => {

console.error(`Failed to fetch posts for user ${user.id}: ${err}`);

});

})

.catch((err) => {

console.error(`Failed to fetch user: ${err}`);

});This is why we have

async and await. These two simple keywords are essentially wrappers around promises that make them look synchronous. The async keyword is used to mark a function as asynchronous, and the await keyword is used to wait for a promise to resmx-auto continuing execution. See this in action:const p = new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve('Hello World!');

})

});

const main = async () => {

const value = await p;

console.log(value); // "Hello World!"

}

main();p is "eagerly" evaluated (that is to say, the callback of the promise is called at the earliest possible opportunity), but this could take time given however long our timeout takes to resolve or reject.It's important to understand exactly how the above could be the same as usingthen and catch callbacks. Note how the function must be declared as async - and await can only be used in functions - this is because the interpreter needs to know that this function will implicitly return a Promise. When you use the await keyword within an async function, it's essentially telling JavaScript to pause the execution of that function until the Promise being awaited resolves. While waiting for thePromise to resolve, the JavaScript engine can continue executing other code outside of this function. When an asynchronous operation is encountered within an async function, it returns a Promise immediately. The await keyword then awaits the resolution of this Promise. If thePromise is already resolved, the execution continues immediately. If thePromise is pending, the async function is paused and control is returned to the event loop, allowing other tasks to execute.

The JavaScript runtime environment, like a web browser or Node.js, has an event loop that continuously checks the state of Promises and other tasks. When a Promise is resolved, it's moved from the pending state to the resolved state, and the event loop schedules the corresponding then callback. When the awaited Promise resolves, the event loop schedules the continuation of the async function's execution. The function resumes from where it was paused by the await keyword. If the awaited Promise is rejected, an exception is thrown, which can be caught using a try/catch block.

Ok mansplainer, what's the problem with Promise.all then?

Promise.all is a function that takes an array of promises and will simply await all of them before returning a resolved promise with an array of all the results. Great! Quite simple, and very handy for cases like the following, where several requests need to be made simultaneously and we want to wait for all of them to complete before continuing execution:

const fetchFoos = async () => {

const fetchFoo = async (id: number) => fetch(`/api/foos/${id}`);

const bar = await Promise.all([

fetchFoo(1),

fetchFoo(2),

fetchFoo(3)

]);

return bar;

}

const main = async () => {

const value = await fetchFoos();

console.log(value); // [...]

}

main();

The problem arises when we handle our errors. If any of the promises fail, the Promise.all will reject with the error of the first promise that fails, however, subsequent promises will still continue to be evaluated - remember what I said about promises being eager beavers?! 🦫

Take the above example, and let's have an error thrown in the second promise:

const fetchFoos = async () => {

const fetchFoo = async (id: number) => {

const result = await fetch(`/api/foos/${id}`);

console.log(id, result);

return result;

}

const bar = await Promise.all([

fetchFoo(1),

Promise.reject('zoinks'),

fetchFoo(3)

]);

return bar;

}

const main = async () => {

try {

const value = await fetchFoos();

console.log(value); // [...]

} catch (err) {

console.log(err); // "zoinks!"

}

}

main();

Promise.all to reject, and the error will be the error thrown by the second promise. However, the third promise will still be evaluated, and the console.log statement will still run. Our output will end up something like:1 Response { ... }

zoinks! // this is our catch block in main!?

3 Response { ... }

The "solution" Promise.allSettled 🫠

You can already see where this is going, I added the quotation marks to make sure you did. The solution isn't great. Functionally, it works, but as a developer who cares about knowing the types of my data at all points in my code, it is unto us a great evil.

Promise.allSettled

Like Promise.all, Promise.allSettled takes an array of promises and returns an array of results. The difference is that Promise.allSettled returns a generic type:PromiseSettledResult. As a type alias you could describe it as the following:

type PromiseFulfilledResult<T> = { status: 'fulfilled', value: T };

type PromiseRejectedResult = { status: 'rejected', reason: any };

type PromiseSettledResult<T> =

| PromiseFulfilledResult<T>

| PromiseRejectedResult;PromiseSettledResult, as an array, will contain either a PromiseFulfilledResult or a PromiseRejectedResult.Nice, an array, clever man, how is our problem solved though?

Let's take a look at a tweaking of our previous example, but this time usingPromise.allSettled:

const fetchFoos = async () => {

const fetchFoo = async (id: number) => {

const result = await fetch(`/api/foos/${id}`);

console.log(id, result);

return result;

}

const bar = await Promise.allSettled([

fetchFoo(1),

Promise.reject('zoinks'),

fetchFoo(3)

]);

return bar;

}

const main = async () => {

try {

const value = await fetchFoos();

console.log(value); // [...]

} catch (err) {

console.log(err); // "zoinks!"

}

}

main();

1 Response { ... }

3 Response { ... }

[{

status: 'fulfilled',

value: Response { ... }

},

{

status: 'rejected',

reason: 'zoinks'

},

{

status: 'fulfilled',

value: Response { ... }

}]

Promise.allSettled is catching our error for us and aggregating it as a PromiseRejectedResult in our array. This is great, and the over all result is considered a fulfilled promise without being unnaturally returned to main! 🎉So wherefore cometh thus the stench!? 🤷♂️

I want to know my types. At all times, I want to know my types. If I don't know my types, a whole new class of issues beyond just "business logic" are introduced. Constant uncertainty. Parallysis! Relatable, right? 🤣

Let's say I want to just get all my fulfilled promises from the array we generated in the above example:

const main = async () => {

try {

const value = await fetchFoos();

const fulfilled = value

// filter out rejected promises

.filter((v) => v.status === 'fulfilled')

// log the value of each fulfilled promise

.forEach((v) => console.log(v.value));

} catch (err) {

console.log(err); // "zoinks!"

}

}

main();

PromiseFulfilledResult objects. It will still think it could be a PromiseRejectedResult object! So there goes our DX that we so desperately craved, and to what we pray to for our own sanity as developers in some vain attempt to keep our code clean and our minds clear.Wise Adam, I'm sure you've thought of a solution, what is it?

And here is where I remind you of a very important programming axiom

your solution will induce a soupcon of back-of-the-throat vomit in the reader, and you will probably be the readerSo, no matter how grim it is, no one will care about that one line as much as you do, so just do it, and don't pester me constantly about trifles.

So here's the best solution my measly brain could come up with:

const main = async () => {

try {

const value = await fetchFoos();

const fulfilled = value

// filter out rejected promises

.filter((v): is PromiseFulfilledResult<Response> =>

v.status === 'fulfilled')

// log the value of each fulfilled promise

.forEach((v) => console.log(v.value));

} catch (err) {

console.log(err); // "zoinks!"

}

}

main();

Conclusion: Promise.allSettled is stinky 🤢

Try as we might, there's not a perfect answer to this problem, especially not in TypeScript. But we can quite easily manouvre around the APIs provided to us and write code that is both readable and safe.

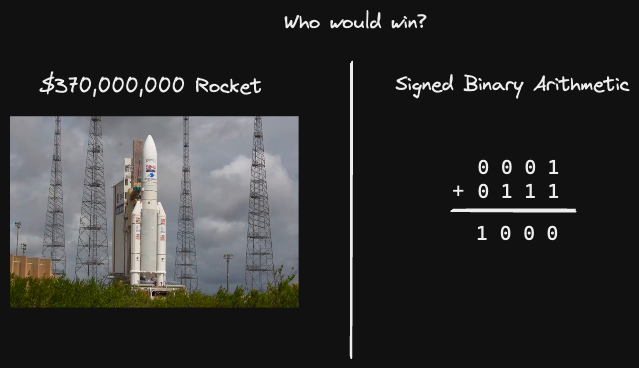

Just don't send your rocket to Mars running TypeScript promises in your inertial reference system. I'm sure it'll be fine, but I'm not sure I'd want to be the one to find out.

Happy absconding! 🚀